(This is an overview of what I hope – or plan – to say for my plenary talk at Interface 2011, 27th July 2011, UCL London. I’m not a fan of reading from the script, so may deviate, hesitate, repeat, and elide on the day. I am told a video will follow, if you’d rather…)

I’m delighted to be here at Interface 2011, and to be partaking – and mixing – with the Digital Humanities community. The title of my talk refers to a few things. Firstly, I’ve not actually done any Digital Humanities for over a year: I’ve been peering at DH from afar, due to being at home doing voluntary work with my own circus troupe (aka “maternity leave”). It is amazing, though, how much you can glean from the twitters, blogs, and email lists whilst up all hours with the bairns, so whilst I have not been hands on, I’ve been closely following the doings and goings on of those who have actively been Digital Humanitiesing.

Secondly, “The Big Tent” was – of course – the theme of DH 2011, which I was unable to attend and am frankly jealous of anyone who did. I was peering at it from afar, and this issue of “Big Tent Digital Humanities” seems to have galvanised discussion in the field about the changing nature of the discipline. I thought is a useful perspective, and definition, to explore (without criticising anyone who organised DH2011).

And finally, “Peering inside the big tent” alludes to the fact that Interface is primarily a conference for graduate students working between the fields of humanities and technology: so many, if not all, of those attending, although still backstage at the moment, aim to be performing front of house in an employed position in the academic circus sooner rather than later. I hope what I say is, then, of use to those nearing the end of graduate studies in DH.

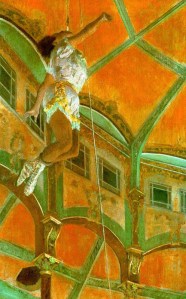

But I want to start with something decidedly non digital. Pre-digital, even. I studied Art History in my undergraduate days, and was thinking of what a career in the humanities meant to students, then. It started with the slide test, where we learnt and memorised hundreds of paintings, and were expected to be able to mobilise knowledge about them expertly. (Note – In the lecture I undertake a slide test here of Degas’ Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, 1879, National Gallery, London). We would study 35mm slides, cramped round a slide cabinet perhaps 5 students deep, for hours, and back this up through print publications and gallery visits. If you caught the bug, you might do your undergraduate dissertation on, say, Degas and his circus paintings. You may then do a MA dissertation on the Impressionists and their circus paintings. If you were good enough, and fortunate to gain funding, you might do your PhD dissertation on the use of perspective in Degas’ circus paintings, and what this “means” for modern art. Eventually, after stiff competition, you may get a post teaching modern (used in the broadest sense) art, and your research would become highly specialised in perspective in impressionist paintings of performance. After years of hard graft you’d own this area, and write in this area, and have found and read every book and article on this area, and publish the elusive monograph in this area. You may have even travelled widely to see every painting in this area in the flesh, not to mention visiting many archives and libraries. It would take years to even piece together all the information you needed to become an expert in the field.

Let’s contrast that to today’s information environment. You are not sure of the exact painting you are interested in, and rather than remember it, a quick google of “degas circus painting” leads you to the Wikipedia page of Miss La La. You can find a link to it at the National Gallery, London, where you can zoom in in so much more detail that you could ever see in a 35mm slide, or even up close when visiting the gallery. You can see where this fits in to the pantheon of Degas’ – and the Impressionists’ – oeuvre by looking up the complete works of all Impressionist paintings, online. The complete works of Edgar Degas shows you every single known study for Miss La La, and you can see high definition images of a pastel study for the painting on the Tate website. You can look up historical newspaper archives to see if there was anything written about the painting or artist in the past, find relevant journal articles that refer to the painting from the comfort of your own laptop, and see if it had been mentioned particularly in any book published since the painting was painted. You could even wander up to the painting virtually using the Google Art Project (well, you will be able to once the NG expand their coverage of Google Art beyond the couple of galleries that have been digitised via street view technology). You can see other’s views and visits of the artwork by a simple Flickr search (which is something art historians love, in particular, for looking at alternative views of sculptures held in museums, beyond the official viewpoint in the print catalogues). If you are in the Gallery, and want more information about a painting, you can simply take a picture on your phone, and search Google with that image, or use Google goggles to tell you more about it. (I am aware that I am mentioning Google frequently: a) I am “not-working” from home and therefore unable to easily access other institutional resources, and b) they do provide an easy suite of tools to use in the first instance, even if there are shortcomings and limitations). You can do a reverse image search using Tin Eye to see who else is talking about that image/ artwork. If you have the access, and resources, you could use advanced imaging techniques to study both the creation and the current condition of the artwork, for conservation purposes and beyond. You could use computational methods to analyse the angles and perspectives of the human figure in Degas’ artworks. You could virtually recreate the Cirque Fernando in 3D to investigate the artist’s perspective of Miss La La. If you didn’t know how to do any of this, you could ask twitter for some pointers, and within minutes someone in the DH community would have responded. Post a question on DH answers, and within 24 hours you would have the best advice on how to study perspective in modern art, using computational methods.

What part of this is Digital Humanities? Is it the act of googling the painting? Using the zoom on the NG website? Using the complete works of Edgard Degas, Google Art Project, JStor, Flickr or even Wikipedia? Is DH the creation of the online resources? The digitisation of books and journals? Is DH the use of tools to study how the painting was created? Composed? Curated? Is DH the study of the use of these tools by users to study art? Is DH the development of techniques and algorithms to analyse the painting? Is DH the means to ask the wider community advice? Is DH the infrastructure which allows the advice to be detailed and delivered to even more scholars? Is DH the use of electronic images of art in powerpoint slides discussing DH? And who is the Digital Humanist? The creator of digital resources? The writer of algorithms? The user of programs? The person who analyses the action of the user? And should academia take any of this seriously?

What is Digital Humanities? And what is Digital Humanities for? To paraphrase Larkin, Ah, solving that question brings the doctors of philosophy in their long coats running over the fields. There is a lot written about this (it’s not the place here to give a history of the definition of DH, but emergent scholars could do worse than make themselves familiar with a lot of the arguments). It’s something to do with the Humanities, and digital technologies, but what exactly, we are slow – and even reluctant – to pinpoint. The latest definition, “Big Tent Digital Humanities”, deliberately obfuscates the focus of the field. Roll up roll up! Everything is Digital Humanities! Everyone is a digital humanist!

The concept of a “big tent” to demarcate a group of individuals is a pragmatic and flexible description usually used to give strength in numbers, permitting a broad spectrum of views or approaches across the constituency. The term has been around for a long time, actually originating from religious American groups in the 19th century (see also “broad church”) rather than the circus background the name implies. It is most commonly applied to political coalitions that have a wide spread of backgrounds, approaches, and beliefs. In some respect it is well suited to Digital Humanities – what are the “Humanities” if not a “big tent” of scholars interested in the human condition and human society? What are the “Digital Humanities” if not a broad spectrum of academic approaches, loosely bound together with a shared interest in technology and humanistic research, in all its guises?

In many regards, “Big Tent Digital Humanities” is a nice concept. It is true that the DH community is considerably more open, approachable, welcoming, and willing to embrace new approaches than many traditional areas of humanities academia. Big Tent DH, then, is an ecumenical approach, whilst giving the freedom for individual scholars to explore their own interests, wherever in the research and teaching spectrum they lie. And why would anyone want to limit the constituency of DH? Surely as technology becomes more and more pervasive in society, finding humanities scholars who do not use any aspect of digital technology in their research will become rarer. As recent blog postings have discussed, anyone who has the interest to do so can tinker with DH, and DH is one of the easiest disciplines to go DIY in. Big Tent DH provides a shared core of likeminded scholars who are exploring digital frontiers to undertake work in the humanities, and welcomes those interested in engaging and learning further about the application of potentially transformative technologies.

But. Just as political parties who are too “big tent” can be criticised for adopting populist policies without any clear remit, stance, or goal, “Big Tent Digital Humanities” has its issues when you look at the detail. It is all very well saying that DH is open and welcoming and encourages participation – but despite open platforms such as DH answers, and the DIY approach, it is still a very rich, very western academic field with a limited number of job openings for the growing number of humanities PhDs that are being produced that have some digital element to them. Let’s be honest: most people undertaking graduate research who want to continue doing research when their studies are finished would like to be paid for it and make it their livelihood, rather than go the DIY, in your own time after the day job, route. I don’t want to dwell on the numbers of PhDs that go onto have academic posts – as far as I’m concerned PhD students should have done their homework on that before undertaking a PhD, and there have always been limited openings. It’s probably true that DH, at the moment, still has more career openings than other, singular humanities subjects. We also have an increasingly popular “#alt-ac” trajectory, where individuals can go on to rewarding alternative academic careers that are not tenure track (what is the alternatives to #alt-ac? #ten-trac-ac? ) However, despite all this, there will be a lot of folk left peering into the Big Tent, without ever gaining full access of any paid employment in DH. Institutional support means access to computational infrastructure, journals, money for equipment, conference travel, paid sabbaticals to write up research, payment which enables you to subscribe to journals and scholarly societies, etc. We should be careful with our descriptions of how open DH actually is, and the resources required to participate in DH research and development, for those without institutional backing. Personally, I don’t like the associations that come with the “Big Tent” label: it paints DH as a transitory spectacle with all the connotations that come with the circus. Branding is important, and (given the experience we in DH have had in trying to be taken seriously by our traditional humanities colleagues) suggesting the field is best described using a big top metaphor, although it may be a bit of fun, is worrying. You don’t see many string theorists describing themselves as “Big Tent Particle Physicists!” – we should be careful what view of ourselves we are projecting into the wider academic world. Our acceptance, even our current fashionable status, has been hard won: and what goes up must come down. Is there really no better way to describe the strengths and objectives of our community?

In lots of ways, though, getting hung up about the term “Big Tent Digital Humanities” is a red herring. Like London buses, there will be another theory – or three – about Digital Humanities along in a minute. However, it is an acceptance that the field is changing, and growing. And therein lies the “crisis” in my title. The field can only continue to expand, as more and more people engage with the technology that allows them to undertake academic tasks, and who are we to ring fence the academic field that lets people discuss this and learn more? Who are we to limit participation in the field to those with paid full time jobs? But if everyone is a Digital Humanist, then no-one is really a Digital Humanist. The field does not exist if it is all pervasive, too widely spread, or ill defined.

As DH expands we run into issues chasing funding (there will always be limited resources, which are now competed for by larger and larger groups of scholars). But perhaps the sticking point that we all most keenly feel, when applied to our own research, is the effect the expansion of DH has on peer review – the essential sifting mechanism around which a discipline functions. There were many vocal complaints on twitter about reviews for papers submitted to DH2011. In some cases, including papers that I was co-author on, the returned reviews varied from high score to dismally low scores – with the comments from the low scorers making it clear that the reviewers did not have the foggiest what the research was about. There is no mechanism to appeal this – and one low score can mean a paper is rejected. The acceptance onto conference programs can spell the difference between attending and not attending conferences, or being published or not being published, and so, in the longer term, career progression. The problem of the Big Tent, or the Broad Church, is that the experience and knowledge of individuals is so loosely bound that “peers” can often have little real insight into the relevance of applicability of a given specific research topic (which, by its nature, should be specialised). As the community around the DH conference expands, this will become an ongoing problem. If everyone is DH, if the field is all encompassing, how can we trust the peer reviews (good or bad) that come from within the community? Does “Big Tent Digital Humanities” mean that DH peer review is broken?

I think there are other, more useful things to concentrate on when defining DH than the “Big Tent” idea. Going back to the pre-digital versus digital scenario given at the start of the lecture: I believe DH has been poor in articulating the changes the digital information environment and its related tools have wrought to humanities scholarship, and the changes and potential that this means for individual scholars. The roles and positions I find myself filling are not those I would have associated with a singular academic career in the pre-digital environment, nor does the publishing avenues of our research chime with the traditional views of the academy (although what did I know then of how academia worked?). Partaking in DH and building a career around its framework means that I have enjoyed researching in many fields: classics, archaeology, history, archival studies, computer gaming, high performance computing, image processing… but unlike the scholars of “old” (all of 15 years ago) I’m very aware I do not own a specialised field, or have a specific research remit, or have the will, means or opportunities to churn out the monographs. DH has allowed me to be jack of all trades, master of none – is this what the Big Tent really means? It is something I have occasionally struggled with, as it would be nice to lay claim to a research area and become noted for work in that area alone. Many digital outputs will never be found on library shelves. Many of the senior scholars in DH, though, have “portfolio” research careers, keeping up to date with developments in technology and applying them variously in different disciplines in ways that would not make tenure in the pre-digital world. Behind the scenes at the Big Tent there are people building interesting, diverse skillsets, and it would be useful at some stage to acknowledge the changing academic role and remit as personified by DH scholars, as well as saying “we’re all DH now”.

The irony is, of course, that the way for young scholars to gain full entry to the Big Tent (whether in #alt-ac or tenure track posts) is still through the specialised focus of PhD research. (Although there are plenty of established scholars in DH without doctorates, even the most perfunctory of positions now usually dictates that applicants hold a PhD in a relevant area). Like an individual circus performer, the individual scholar must become the expert in their chosen, niche area, and hone their own skill and approach. However, if there is one piece of advice I can give to those embarking on an academic career, it is to look around the Big Tent, and to see what skills are most needed, asked for, and employable, and to make sure that these are also part of your skillset. For example, I have no research interest in textual encoding and markup, but I make sure that I follow the gist of what is going on with the technology, and would be able to teach it. XML and TEI are such a core part of any DH teaching program that it would be remiss not to have experience in this area. Make sure you know the basics of Internet Technologies, Databases, and even GIS. Experiment with programming, at least just to see what it is about. You may not believe it at the moment, but Graduate students have the luxury of time to pick up and learn new skills beyond your immediate research. Use whatever training courses your institutions offers wisely, while you have the opportunity. Once you hit employed life, the time and opportunity to develop your skills in such a wide manner becomes severely rationed.

Make sure you are visible in Social Media circles (show that you are actively peering in, before applying for positions). Engage with others doing different DH research: use the Big Tent as a way to network with people, whilst seeing what new technologies are being appropriated within DH. Make sure you make yourself ready for employment: a cursory glance at employment adverts for DH will show that those with job openings are asking for a lot. I wonder if the spread of topics and skills demonstrated in the Big Tent constituency mean we are almost asking too much from individual applicants at the very start of their careers: you want to join the circus? Show us you know how it all works!

My second piece of advice would be – read “Alternative Academic Careers for Humanities Scholars” (edited by Bethany Nowviskie). Understand the arena you want to be employed in, and the various approaches there can be there to getting jobs there.

My final piece of advice is – learn to touch type. If you are planning to be a professional Digital Humanist, there is a whole lot of silicon-face time to be spent. Invest in your future by learning how to engage with the digital in the fastest and most efficient way possible (at the moment).

And then I should probably all wish you good luck out there, but I’m going to end with the painting of Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando. It’s the analysis of such objet, and the potential for digital techniques and technologies to aid us in understanding different perspectives of the human condition that drives Digital Humanities. But it is also about tenacity, and application, and hard work, and expertise. There’s not much “luck” in the skill demonstrated by Miss La La in this painting: its sheer, hard won, strength and agility. Despite all the “Roll up! Roll up!” talk and advertising, the wonder comes down to whether or not she can actually apply herself, and undertake the task. It’s the same for Digital Humanists: despite the changing definitions and perspectives that surround our field, the value and usefulness of our skills are demonstrated through what we actually do, the research we undertake, the tools we build, the people we teach, the literature we write.

I am looking forward to actually doing Digital Humanities again. It is in the doing that we can explore what the changing information environment means for the Humanities, and scholars in the Humanities. We can argue the limits and boundaries of our constituency, and the list of essential skills that make up DH, over and over. But as digital technologies become increasingly pervasive, the work and skills of Digital Humanists become increasingly important. We are holding on tight to our place in academia – by our teeth, if needs be.