I’m pleased to say that we’ve won a Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities (SGSAH) 3.5 year scholarship for a PhD student, looking at how we can embed Handwritten Text Written software into digitisation practices, whilst supporting users, working with Transkribus and the National Library of Scotland. The advert will go live soon on our official channels – but for now – here are the details and I’d appreciate folks sharing with any interested EU or UK Master’s students! Closing date of 22nd June. Thank you!

—

The University of Edinburgh, the National Library of Scotland, and the University of Glasgow, in conjunction with the READ-COOP, are seeking a doctoral student for an AHRC-funded Collaborative Doctoral Award, “Adopting Transkribus in the National Library of Scotland: Understanding How Handwritten Text Recognition Will Change Management and Use of Digitised Manuscripts”. The project has been awarded funding by the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities (SGSAH) and will be supervised by Professor Melissa Terras (College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Edinburgh), Dr Paul Gooding (Lecturer in Information Studies, University of Glasgow), Dr Sarah Ames (Digital Scholarship Librarian, National Library of Scotland) and Stephen Rigden (Digital Archivist, National Library of Scotland).

The studentship will commence on 14th September 2020. We warmly encourage applications from candidates with a background in digital humanities, information studies, library science, user experience and human computer interaction, history, manuscript studies, and/or palaeography. This is an extraordinary opportunity for a strong PhD student to explore their own research interests, while working closely with a major cultural heritage organisation, two world-leading universities, and the team behind Transkribus (https://transkribus.eu/Transkribus/), the machine learning platform for generating transcripts of historical manuscripts via Handwritten Text Recognition.

The student will be based in the School of Literature, Languages and Cultures, at the George Square campus of the University of Edinburgh, but will also spend considerable time at the National Library of Scotland, and liaising with the Transkribus team (based at the University of Innsbruck). Much of the research can be undertaken offsite.

The student stipend is approximately £15,285 per annum + tuition fees for 3.5 years. The award will include a number of training opportunities offered by SGSAH, including their Core Leadership Programme and additional funding to cover travel between partner organisations and related events. This studentship will also benefit from training, support, and networking via the Edinburgh Centre for Data, Culture and Society, and the Edinburgh Futures Institute. The student will be invited to join National Library PhD cohort activities.

Project Details

“Adopting Transkribus in the National Library of Scotland: Understanding how Handwritten Text Recognition Will Change Management and Use of Digitised Manuscripts”

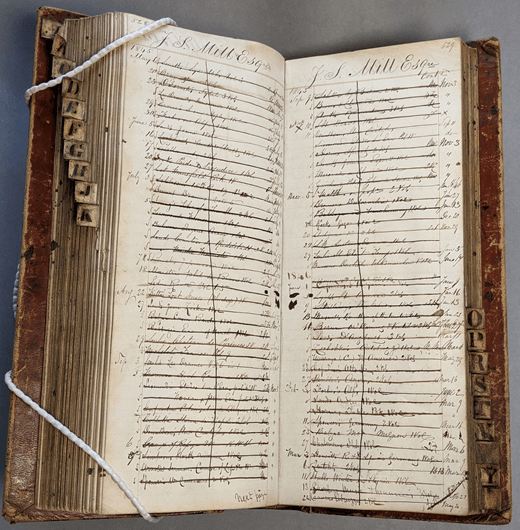

Libraries are investing in mass digitisation of manuscript collections but until recently textual content has only been available to those who have the resources for manual transcription of digital images. This project will study institutional reception to machine-learning processes to transcribe handwritten texts at scale. The use of Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) to generate transcripts from digitised historical texts with machine learning approaches will transform access to researchers, institutions and the general public.

The PhD candidate will work with the National Library of Scotland and its user community to gain a holistic view of how HTR is changing access to the text contained within digitised images of manuscripts, from both an institutional and user context, at a time when the Library is scaling up its own mass digitisation practices. A student placement at the National Library of Scotland will link this to wider research questions. The candidate will learn how to use Transkribus at an expert level, work closely with the digital team at the National Library of Scotland to understand how best to apply HTR within a heritage digitisation context, and investigate how best to encourage and support the uptake of this technology with users of digitised content. This will result in a holistic, user focused analysis of the current provision of HTR, while also assisting the National Library of Scotland and other cultural heritage institutions in being able to understand how best to deploy this new technology in an effective manner, understanding implications for themselves, and their users, as well as contributing to the growth of the only freely available HTR solution currently available for the heritage community.

This CDA therefore gives unique access to a rapidly growing community, and tool for historical research, which has not yet been studied from a user or institutional perspective. The outputs of this research will be of use to both the National Library of Scotland, other institutions using HTR, those considering this approach, and the READ-COOP, who manage Transkribus.

Eligibility

At the University of Edinburgh, to study at postgraduate level you must normally hold a degree in an appropriate subject, with an excellent or very good classification (equivalent to first or upper second class honours in the UK), plus meet the entry requirements for the specific degree programme (https://www.ed.ac.uk/studying/postgraduate/degrees/index.php?r=site/view&edition=2020&id=254). In this case, applicants should offer a UK masters, or its international equivalent, with a mark of at least 65% in your dissertation of at least 10,000 words.

To be eligible to apply for the studentship you must meet the residency criteria set out by UKRI. For further details please see the UKRI Training Grant Guide document, p17.

The AHRC also expects that applicants to PhD programmes will hold, or be studying towards, a Masters qualification in a relevant discipline; or have relevant professional experience to provide evidence of your ability to undertake independent research. Please ensure you provide details of your academic and professional experience in your application letter.

Prior experience of digital tools and methods, an understanding of digitisation and the digitised cultural heritage environment, use of qualitative and quantitative research methods, and an experience of palaeography, history, or interest in historical manuscript material will be of benefit to the project. However, this is not a prerequisite so while preference may be given to candidates with prior experience in these areas, others are warmly encouraged to apply.

Application Process

The application will consist of a single Word file or PDF which includes:

- a brief cover note that includes your full contact details together with the names and contact details of two referees (1 page).

- a letter explaining your interest in the studentship and outlining your qualifications for it, as well as an indication of the specific areas of the project you would like to develop (2 pages).

- a curriculum vitae (2 pages).

- a sample of your writing – this might be an academic essay or another example of your writing style and ability.

Applications should be emailed to pgawards@ed.ac.uk no later than 5pm on Monday 22nd June. Applicants will be notified if they are being invited to interview by Thursday 2nd July. Interviews will take place on Thursday 16th July via an online video meeting platform.

Further information

If you have any queries about the application process, please contact: pgawards@ed.ac.uk. Informal enquiries relating to the Collaborative Doctoral Award project can be made to Professor Melissa Terras.

More Info:

Libraries and archives are investing in digitisation of manuscript collections at scale, but until recently transcriptions of digitised texts have only been available to those with the resources to manually transcribe individual passages. AI is now used within archives for a growing range of tasks: tagging of large image sets; detecting specific content types in digitised newspapers; discovering archival materials; and supporting appraisal, selection and sensitivity review. Successful machine learning approaches to transcribing images of historical papers by Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) will transform access to our written past for the use of researchers, institutions and the general public.

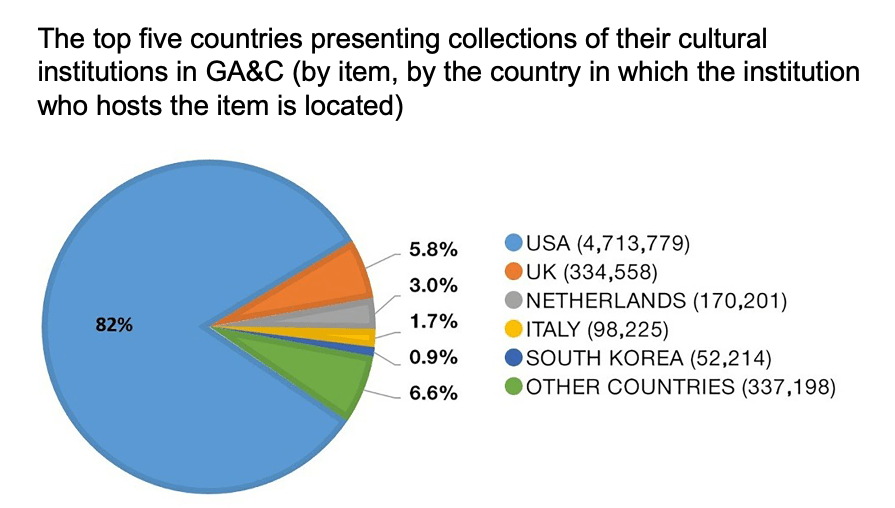

This project will explore how Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) can be embedded into digitisation workflows in a way that best benefits an institution’s users. Transkribus (https://transkribus.eu/Transkribus/, currently the only non-commercial HTR platform capable of generating transcriptions of up to 98% accuracy, will be used as the research foundation. Transkribus is the result of eight years of EU funded research into the automatic generation of transcripts from digitised images of historical text through the application of machine learning. There are now 25,000 Transkribus users, including individuals and major libraries, archives and museums worldwide (https://read.transkribus.eu/network/). Recently, a not for profit foundation (READ-COOP https://read.transkribus.eu/about/coop/) has been established to ensure that the Transkribus software will be sustained. While recent publications have considered HTR from the perspective of platform development (Muehlberger et al., 2019 https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JD-07-2018-0114/full/html), there has been no research published to date on how user communities are using HTR, the effect this will have on scholarly workflows, and the potential HTR has for institutions.

The project will partner with the National Library of Scotland, with support from its Digital and Archives and Manuscript Divisions. This will enable the student to pursue relevant areas of interest, such as:

- Experience and analyse the staged processes of digitisation workflows in context;

- Apply an understanding of HTR to the delivery and presentation of transcribed material online;

- Work with digitised cultural archival resources, using HTR to generate transcriptions;

- Apply ethnographic approaches to understand how HTR relates to traditional palaeographic practice;

- Identify and work with the Library’s user communities and undertake user experience testing with them to evaluate barriers and opportunities.

This will result in a holistic, user focused analysis of the current provision of HTR, while also assisting The National Library of Scotland and other cultural heritage institutions in being able to understand how best to deploy this new technology in an effective manner, understanding implications for themselves, and their users.

The successful student is likely to have relevant experience and qualifications. This might include qualifications in Library and Information Studies, Computer Science, Human Computer Interaction, Digital Humanities or cognate disciplines. They are likely to have knowledge of the Library and Archival sector gained either through professional or academic engagement. Alternatively, an appropriately strong academic background in addition to professional experience of the library sector and/or software development for cultural heritage organisations could substitute for specific qualifications. The placement part of the PhD will be carefully tailored to complement the candidate’s existing skillset, and the National Library of Scotland will give the opportunity to understand both existing digitisation workflows, and to contribute to discussions of future embedded use of HTR.

The University of Innsbruck is the home of Transkribus, and is coordinating the READ COOP. There will be opportunities within this studentship to visit Innsbruck, particularly for the Transkribus annual user conference, and to liaise with the team about developments with the software, including spending time with and in regular contact with the delivery team to understand how the Transkribus infrastructure operates. This will be done with full knowledge and support of the PhD supervisors.

My

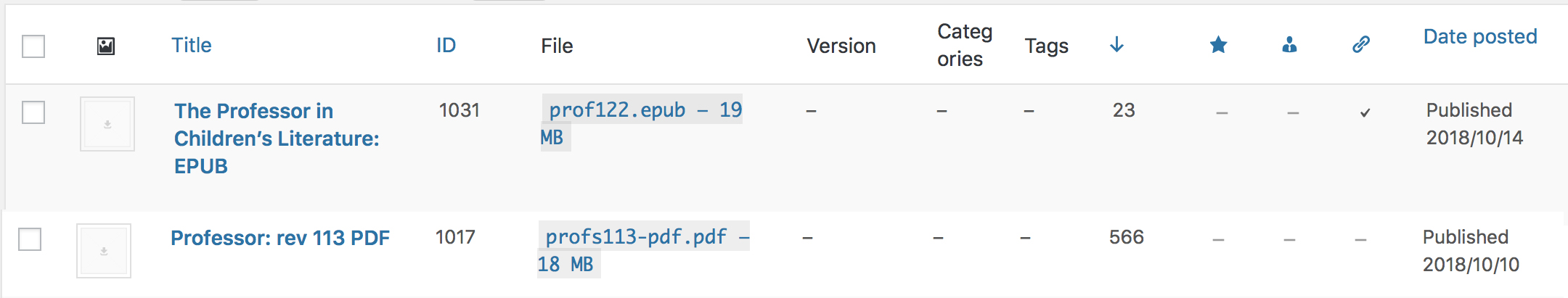

My  The anthology project was always about marrying open access with digitisation, to provide a means of showing your working out in the humanities, akin to the open-science approach to making your data available. I’m very proud of this anthology (although I learned that putting anthologies together is much harder work than it looks!)

The anthology project was always about marrying open access with digitisation, to provide a means of showing your working out in the humanities, akin to the open-science approach to making your data available. I’m very proud of this anthology (although I learned that putting anthologies together is much harder work than it looks!)